Yesterday on Twitter, I took part in an impromptu discussion of fraction multiplication. I’ll be honest. I often get frustrated diving deeply into meaty topics on Twitter because I’m limited to 140 characters per tweet (less when you take into account the fact that the handle of everyone tagged in the tweet is deducted from the total). However, this ended up being a very enjoyable conversation and reminded me of the power of connecting with folks from all over.

Tracey Zager was nice enough to Storify the conversation. If you’re interested to hear how a small group of elementary educators unpacked this topic, take a look. If you’re an elementary teacher yourself, especially an upper elementary teacher, you may appreciate it because you’re likely having similar conversations within your own district or campus.

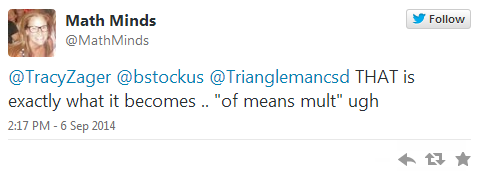

One question that came up several times during the conversation was how and why the word “of” means multiplication:

As Math Minds’ tweet alludes to, there is a whole issue of teaching keywords and the damage they cause students, but that’s not what I’m focusing on here. Today I want to think through the idea of how the simple two-letter word “of” is related to the operation of multiplication in the first place.

This question made me think of the chapter I’m currently reading in Kathy Richardson’s book How Children Learn Number Concepts: A Guide to the Critical Learning Phases. It’s very timely that I’m reading a chapter titled “Understanding Multiplication and Division”. Richardson begins the chapter with the following quote from Keith Devlin (I like that I’m quoting a quote from a book.):

“…in today’s world we are faced with a great many decisions that depend upon an understanding of quantity. Some of them are inherently additive, some multiplicative, and some exponential. The behavior of those three different kinds of arithmetical operations differs dramatically…”

Richardson goes on from there to discuss the need for elementary teachers to differentiate additive and multiplicative thinking.

“Central to understanding multiplying is the idea that the two numbers (factors) in a multiplication equation have two different meanings: one number describes how many equal groups there are and the other describes the size of each of the groups.”

And when we describe the relationship between the two numbers verbally, the word “of” can become an essential part of our description. Here’s an example from Ask Dr. Math:

Suppose items come 8 to a box.

If I have 2 of these 8’s, I multiply to find the total, 2 × 8 = 16.

(There are 2 equal groups and the size of each group is 8.)

If I have ½ of an 8, I multiply: ½ × 8 = 4.

(There is ½ of a group and the size of the group is 8.)

Going back to Richardson’s book, she goes on to describe the types of multiplication situations students should encounter in elementary school:

- Equal groups (equivalent sets)

- Rate / Price / Length

- Rectangular arrays

- Multiplicative comparison (scale)

- Combination problem (Cartesian product)

It’s the multiplicative comparison (scaling) situations that lend themselves best to understanding fraction multiplication. I found it very telling that in the CCSS grade 4 Operations & Algebraic Thinking domain, there is a standard that says students should interpret multiplication as a comparison. The standard uses whole numbers in its example, but the pump has been primed. Then in grade 5, this idea is embedded in the Number & Operations – Fractions domain in a standard that says students should interpret multiplication as scaling (resizing).

The trouble seems to be that up until fraction multiplication, the act of multiplying two whole numbers has always resulted in a larger number, and it has been easy for teachers and students to view it as repeatedly adding that quantity over and over. However, this idea of a quantity growing larger through repetition is only half of what’s going on. If quantities can grow larger, then they can also grow smaller, and our language to describe this needs to adjust accordingly. Instead of having 3 times as much or double the amount, we can now consider 2/3 of a quantity or half as much.

I don’t think the problem is that the word “of” doesn’t mean multiplication per se, but that as elementary educators, we haven’t opened ourselves up to needing different language to describe something new students are learning to do, namely using the operation of multiplication to decrease the size of a quantity.

Although, after writing all that, I want to revise my thinking. Richardson goes on to describe how children have difficulty grasping the word “times” when they first learn about multiplication. She recommends teachers use phrases such as “groups of”, “rows of”, “piles of”, “stacks of”, etc. There’s that word “of” again, and Richardson is advocating using it with children well before they learn about fraction multiplication.

If students can visualize and make sense of:

- 2 groups of 5

- 3 rows of 6

- 7 piles of 10

- 3 stacks of 9

Then we should be able to extend to this later on:

- 1/2 group of 5

- 2/3 row of 6

- 1/10 pile of 10

- 1/3 stack of 9

We come back to the idea that the two numbers in a multiplication situation have two different meanings. The first number in each example is the number of groups, whether it’s 2 groups or 1/3 of a group. The second number is the size of one whole group, whether the whole group is 4 pans of brownies or 1/3 pan of brownies.

So ultimately it seems that the word “of”, and phrases built around it, are mostly there to help students to visualize and make sense of a new kind of thinking. Up until grade 3, most students have been focused on additive thinking, so this is quite the paradigm shift for them, and they will grapple with it for several years. As a result teachers need to use familiar language and phrases, which include the word “of”, to help students expand their understanding of how we operate on quantities.

This was a great exchange of ideas and thoughts. it’s astonishing how loaded a little word like “of” can be. This has also been something that has troubled me, and your post and Tracy’s “storification” of the Twitter conversation has helped me sort it out a bit.

The nexus of language and math is a fascinating place. We have to be very careful about what we say and how we say it.

I agree. Language, while meant to articulate and clarify, can also serve to muddy and confuse. It reminds me of Keith Devlin’s MOOC where he emphasized the need for precision in language, though he was focused on college level math. At elementary grades, I believe connecting informal language to formal concepts can be very beneficial to students. However, the eventual move to symbolic representations seems to be a way to move them beyond the confusions brought about by our language.

Re: “connecting informal language to formal concepts.” So kids to come up with names that make sense to them first, then once the concept or idea has been solidified the definition is formalized? I like this approach. We introduce the vocab up front when we should be waiting till the end. I tried this out last year with “prime” and “composite” with some 4th graders as an experiment.

http://exit10a.blogspot.com/2014/06/the-world-would-be-great-place-if-we.html

I am using the phrasing “of ” for percentages. What percentage is 5 of 10. This sets up the division in the right order. My students struggle with that. Percentage is a comparison. I have started drawing bar charts to show the concept of percentages being measures of portions of wholes. There is that “of” again!

Pingback: Elementary Teachers as Math Learners | Becoming the Math Teacher You Wish You'd Had

Pingback: Why | Math Minds

Just found this !

I like it !

If we see math as an attempt to codify and organize numerical ideas then, really, “multiply” means “of”.

That is to say that we have a new formal word to describe an existing action.

It’s almost as bad with plus and add.

Here is A. N. Whitehead in 1911 on the subject of negative numbers:

http://howardat58.files.wordpress.com/2014/08/whitehead-intro-to-math-negative-nos.doc

His basic idea is that numbers are operators, so the +4 in 3+4 means “add 4”.

Thinking about commutativity gives me pause here. If one way of thinking about multiplication is to think of one number being group size while the other is the number of groups, then how do I make sense of this within the context of commutativity? Entirely possible that I am missing something obvious, but this jumped out at me when I read your post.

The whole issue of multiplication and how we can get students to understand it fascinates me. I like howardat58’s point: It’s not so much that we want students to think “of” means multiply, as the reverse—that when they see the abstract times symbol between two quantities, they can think of it as “of”, especially in situations involving fractions and percents. It gives them a way to visualize what the numbers are doing.

Mr. Dardy: Somewhere I read that we adults take the commutative nature of multiplication too much for granted, that it *should* be a strange and surprising result to our students. Wish I could remember who said that…