Last spring I wrote about how over the past few years I’ve continually revised and refined the scope and sequence of elementary mathematics in grades K-5 in my school district. You can read those posts here:

The tl;dr version is that I concluded the series in May 2018 with these parting thoughts:

…what started as a blog series where I was planning to reflect on the changes I might make for next year has instead reaffirmed that the work I’ve done with my teachers over the past three years has resulted in six scope and sequences that make sense and don’t actually require much tweaking at all. I’m proud of what we’ve accomplished. Are they perfect? Probably not. But they appear to be working for our teachers and students, and at the end of the day that’s what matters.

Source

Fast forward to this post I wrote reeling from my experiences at the Math Perspectives Leadership Institute in late June:

There is a HUGE disconnect between what [Kathy Richardson’s] experience says students are ready to learn in grades K-2 and what our state standards expect students to learn in those grades. I’ve been trying to reconcile this disconnect ever since, and I can tell it’s not going to be easy… I’m very conflicted right now. I’ve got two very different trajectories in front of me… Kathy Richardson is all about insight and understanding. Students are not ready to see…until they are. “We’re not in control of student learning. All we can do is stimulate learning.” Our standards on the other hand are all about getting answers and going at a pace that is likely too fast for many of our students. We end up with classrooms where many students are just imitating procedures or saying words they do not really understand. How long before these students find themselves in intervention? We blame the students (and they likely blame themselves) and put the burden on teachers down the road to try to build the foundation because we never gave it the time it deserved.

Source

What a difference a month makes.

In May I was feeling proud and confident of the work I’d accomplished developing and revising our elementary scope and sequence documents. A month later I’m calling everything into question and having a crisis of conscience about whether the scope and sequences I’ve planned are actually creating some of the struggles I was trying to prevent.

Back in July I closed my post with no answers:

But how to provide that time? That’s the question I need to explore going forward. If you were hoping for any answers in this post, I don’t have them. Rather, if you have any advice or insights, I’d love to hear them, and if I learn anything interesting along the way, I’ll be sure to share on my blog.

Source

This big question of how to reconcile the pace of learning for our youngest students with the pace of the state standards has been on my mind for months. Throughout the fall semester, I had countless conversations with colleagues in and out of my district. These conversations culminated in my taking a stab at revising our scope and sequences in grades K and 1 as well as proposing a new instructional model in grades K and 1. (Ultimately I made revisions to the scope and sequence documents for grades K-4, but I’m going to focus on K and 1 in this post.)

I’ve been sharing, talking about, and revising these document with teachers, instructional coaches, and curriculum specialists in my district for a couple of months now, and I feel like they’re finally in a shape that I want to share them here so you can see where all of this thinking has taken me since I last wrote about this in July.

As a point of reference, here are the Kindergarten and 1st grade units for the 2018-19 school year.

Kindergarten 2018-19

1st Grade 2018-19

Our curriculum is now open to the public, so if you’re interested in visiting any of these units to see unit rationales, standards, lessons, etc., you can do that here.

Contrast that with these proposed units for the 2019-20 school year:

Proposed Kindergarten 2019-20

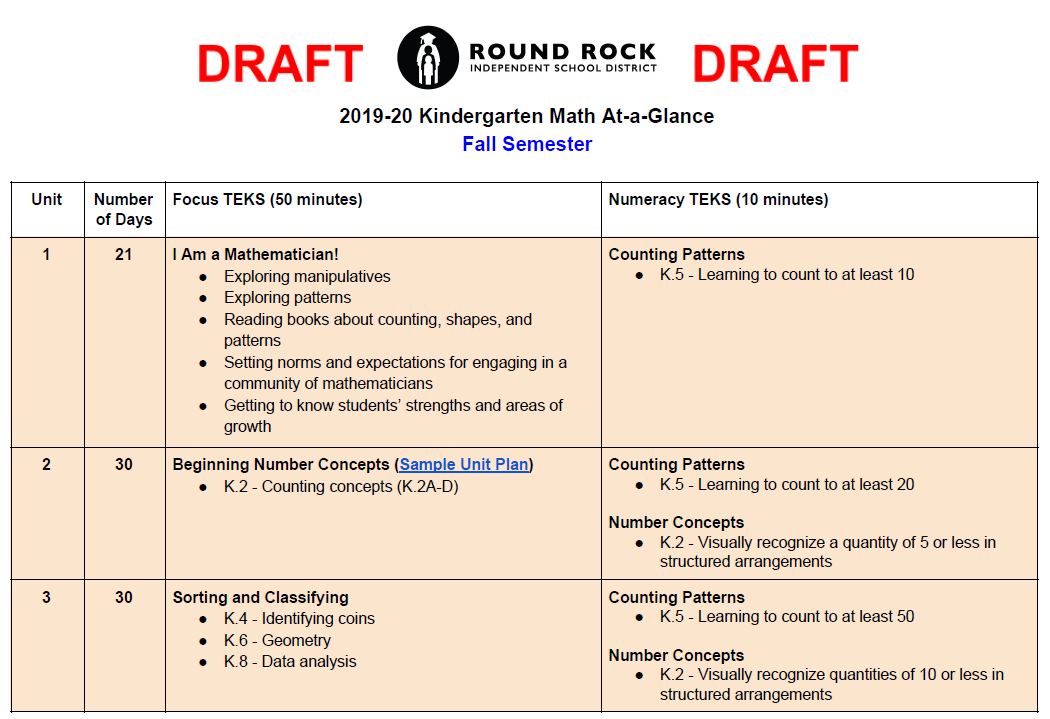

- Fall Semester

- Unit 1 – I Am a Mathematician! (21 days)

- Unit 2 – Beginning Number Concepts (30 days)

- Unit 3 – Sorting and Classifying (30 days)

- Spring Semester

- Unit 4 – The Concepts of More, Less, and the Same (30 days)

- Unit 5 – Joining and Separating Quantities (30 days)

- Unit 6 – Building Number Concepts (30 days)

Proposed 1st Grade 2019-20

- Fall Semester

- Unit 1 – I Am a Mathematician! (15 days)

- Unit 2 – Adding and Subtracting (30 days)

- Unit 3 – Exploring Shapes and Fair Shares (27 days)

- Unit 4 – Understanding Money (10 days)

- Spring Semester

- Unit 5 – More Adding and Subtracting (20 days)

- Unit 6 – Collecting and Analyzing Data (10 days)

- Unit 7 – Introducing Unitizing (15 days)

- Unit 8 – Exploring the Place Value System (24 days)

Here are some of the changes and my rationale for them:

- In Kindergarten we drastically reduced the number of units. Instead of 10 units, we’re down to 6. On top of that, the first unit has shifted from counting concepts to “I Am a Mathematician!” What does that mean? Here are the notes I took to describe this unit:

- Exploring manipulatives

- Exploring patterns

- Reading books about counting, shapes, and patterns

- Setting norms and expectations for engaging in a community of mathematicians

- Establishing routines

- Getting to know students’ strengths and areas of growth

- I made the names of the units more vague. Rather than stress teachers out that their students should be counting to 5, then 10, then 20 in lockstep, I’m providing space for students to engage in number concepts in general. Teachers can differentiate as needed so students who need to work within 5 can continue to do that while other students are exploring 8 or 12 or 14.

- I made the units in Kindergarten longer to give students time to “live” in the landscape of these concepts. This goes hand-in-hand with the new instructional model I’m proposing based on the work of Kathy Richardson. Now a typical day will include a short opening activity that’s done together as a whole class. The bulk of math time will be spent in an explore time where students self-select activities that are variations on the core concept of the unit. During this explore time, the teacher’s primary role is to confer with students and continually nudge them along in their understanding. Each day there is a short lesson close to help students reflect on their learning. Here’s a link to a sample suggested unit plan to help teachers envision what a unit might look like in grades K and 1. (Note: If you encounter a link you can’t access in the document it’s likely due to copyright that we don’t control.)

- In 1st grade I reduced the number of units focusing on addition and subtraction. Similar to number concepts in 1st grade, I want to give students an extended amount of time to “live” in these concepts.

- In 1st grade I moved place value to the very end of the year. According to Kathy Richardson, unitizing and place value topics are challenging for 1st graders. However, I have to include them because our state standards require it. In order to reconcile this, I want to give students as much of the year as possible for their brains to develop so they are working with the most up-to-date hardware when they start learning these critical concepts. Putting it at the end of the year also creates more proximity to when students will continue learning about place value in 2nd grade. I’ve even added a 2-digit place value unit to our 2nd grade scope and sequence to create a bridge and continue the learning.

- In 1st grade, I created a unit just on unitizing and followed that up with a unit on place value. Using activities from Kathy Richardson’s Developing Number Concepts series, students will spend three weeks making, naming, and describing groups of 4, groups of 5, groups of 6, and eventually groups of 10. Then they’ll spend almost five weeks extending this as they learn how our place value system is built on groups of 10.

The units are just the tip of the iceberg. The math block in our district is 80 minutes and broken up across three components:

- Focus Instruction (50 minutes)

- Numeracy (10 minutes) – This used to be named Computational Fluency but I’m re-branding it because the names imply different goals.

- Spiral Review (20 minutes)

So when I revised the scope and sequence documents, I also revised the learning across all three components.

Draft Kindergarten At-A-Glance 2019-20

Draft 1st Grade At-A-Glance 2019-20

Things to point out:

- I’ve settled on a few anchor instructional routines across all grade levels – number talks, choral counting, and counting collections. That’s not to say that teachers can’t use other routines – I encourage them to – but my goal is to ensure that these three powerful, versatile routines are in everyone’s toolbox.

- Kindergarten only has 60 minutes of math instruction in the fall semester so they don’t start spiral review until the spring semester.

- In 1st grade the numeracy topics are fairly consistent across the year – skip counting, subitizing, making 10, and developing strategies for adding and subtracting within 20. My hope is that the consistency of topics across the year paired with the anchor instructional routines will allow the numeracy work to feel more like an ongoing conversation across the year.

- In 1st grade creating, solving, and representing addition and subtraction problems is a spiral review topic over and over again. I want to ensure students have lots and lots of opportunities to engage with problems involving joining, separating, and comparing quantities.

Parting Thoughts

Now that I’ve started to get a plan in place, I have a lot of work ahead of me to create all the associated unit documents. I’m also going to be working on gathering teachers who want to pilot these new units. I’m wary of just dumping them on our teachers because they’ve already put so much work into learning the old units, and there are some heavy instructional shifts that might need to be made to make these units work. Thankfully I don’t think it will be too hard to find volunteers. Teachers who’ve looked at these plans and talked about them with me or their instructional coach have been really excited for the changes, so much so that I have an entire Kindergarten team trying out one of the new units right now!

While there are still a lot of unknowns and a lot of work ahead to support teachers, I do feel like all of the reflecting, conversations, and attempts at making a new plan over the past six months have brought me to a place where I feel like I’m moving in a good direction that I’m happy to follow for the time being.

Here’s to the path ahead.